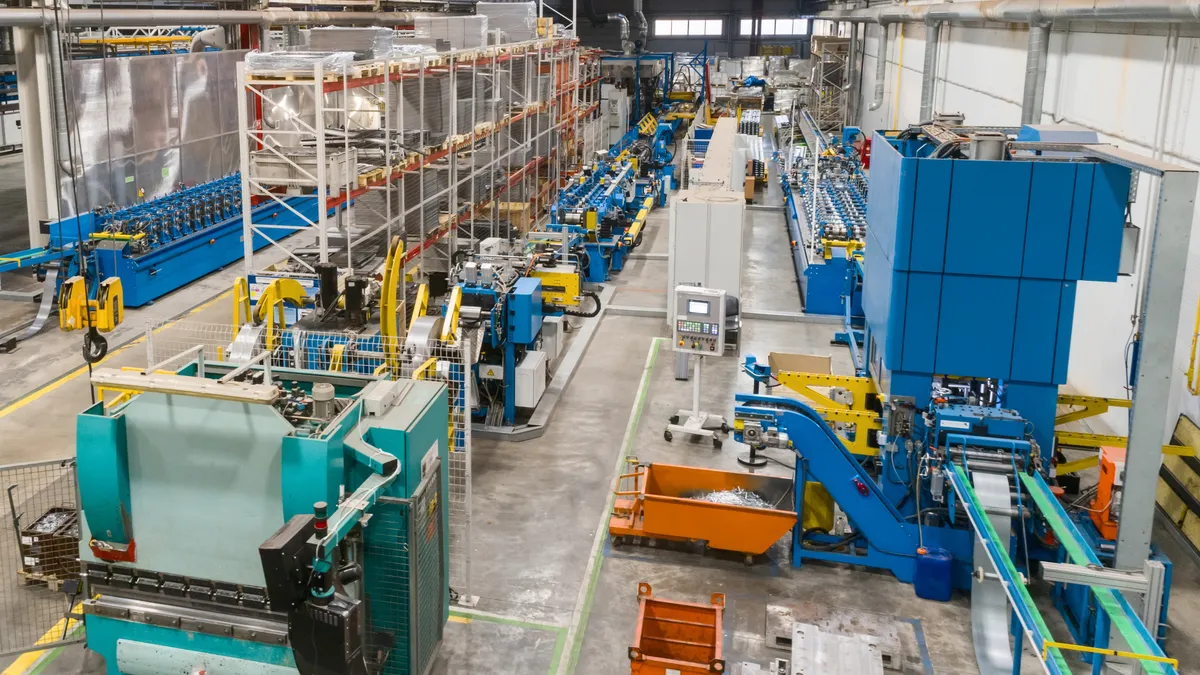

A muted fall economy weighed down manufacturers’ expectations in October, leading companies to shift their staffing levels and capital expenses.

The murky outlook was reflected in two purchasing managers’ indices released Wednesday, which paint a picture of manufacturers lowering staffing levels, among other tactics, to adjust to the sector’s prolonged contraction.

The Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing PMI registered a reading of 46.7%, down 2.3 percentage points from September. A reading of 50.0% or lower indicates the industry is in economic contraction.

The decline marks a reversal from the previous month’s trend, when the index grew slightly and showed signs for optimism, though the industry remained in contraction. Manufacturing has now been contracting for twelve consecutive months, per the report.

"We normally don't stay below the 50 line this long,” said Timothy Fiore, chair of the Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing Business Survey Committee, on a call with reporters Monday. “Most of the times we’ve had these contractions, they’ve been 5 to 6 months.”

The bleak performance was driven by soft demand, and declines in new orders and employment levels. Fiore said manufacturers surveyed for the index used layoffs as their primary tool to manage headcount, compared to prior months when companies relied on attrition.

Low expectations for the economy may also be driven by a weak level of new orders, which fell 3.7 percentage points during the month. The figure, coupled with a slight decrease in companies backlog, could lead build-to-order manufacturers without high expectations for future demand, said Fiore.

The brunt of the changes to new order levels were reported by manufacturers in the computer electronics, machinery and fabricated metal product sectors. The fact all three are capital intensive industries is significant, said Fiore, as it could suggest an uncertain economy and tighter monetary policy is leading manufacturers to lower their capital expenditure projections.

“Many of them have longer lead times, do build to order, and at present the orders are not there,” said Fiore. “That’s a concern about investments in the future, which really leads to productivity improvements as well as capacity expansion.”

Yet despite concerns about the future, there were some positive indicator’s in ISM’s October report: production remained at growth levels, and supplier deliveries are getting faster, though they are still in contraction.

The S&P Global US Manufacturing PMI was more optimistic, as the index marked the second month of growth and stabilized at a reading of 50.0 in October. The reading of 50, which suggests the industry is no longer in decline, ends a five-month period of manufacturing contraction per that index.

In contrast to the ISM index, S&P Global reported rising new order levels, driven by an increase in domestic demand. However, economists were quick to point out concerns over a decrease in employment levels and tempered future expectations remained.

“Of concern were reports of dwindling backlogs of work, previously used to help support production, as firms also revised down their expectations for future output to the lowest in 2023 so far,” Siân Jones, principal economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence, said in a statement attached to the index.

The decline in future expectations also affected staffing levels. Jones said “manufacturers cut employment for the first time in over three years as workloads were reportedly insufficient to warrant additional hiring or the replacement of voluntary leavers.”