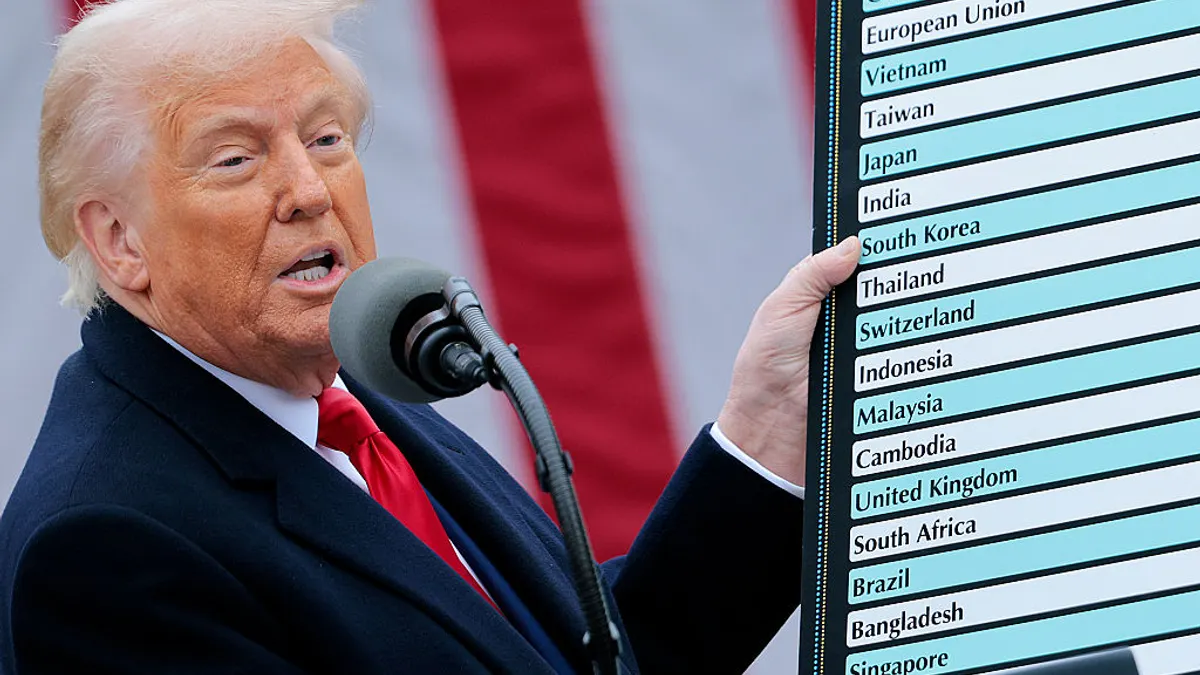

President Donald Trump’s aggressive implementation of country-specific tariffs will face Supreme Court scrutiny next month.

At stake will be Trump’s broad use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to enact sweeping levies. Two federal courts have already ruled such actions illegal, leading the Trump administration to file appeals, including a request for the Supreme Court to consider the cases. The high court is scheduled to hear arguments in November.

The administration has argued that the president’s utilization of IEEPA to impose tariffs is justified due to national emergencies Trump has declared related to trade deficits and fentanyl trafficking. More broadly, the administration contends that because Congress passed IEEPA, it has oversight authority, not the courts.

Through its interpretation of IEEPA, the Trump administration has been able to set tariffs on a wide range of U.S. trading partners without additional bureaucratic machinations. The administration has also cited IEEPA to hike previously enacted tariffs, such as combined tariffs of 50% on India imports.

“I think part of the attraction of IEEPA was that there's no report,” said Alexander Schaefer, a partner in the international trade group at law firm Crowell & Moring. “There are no findings that have to be made. The president declares an emergency and then says, ‘Here's what we're going to do about it,’ and without any sort of procedural red tape to have to go through.”

The Trump administration has not relied solely on IEEPA to advance its tariff regime, and regardless of the Supreme Court’s decision, the president still retains several tools to continue hiking levies. Here’s a look at some of those mechanisms and how the Trump administration could employ them.

Section 232

In parallel with its IEEPA tariffs, the Trump administration has also relied heavily on Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to enact tariffs and initiate investigations on certain sectors.

“I think part of the attraction of IEEPA was that there's no report."

Alexander Schaefer

Partner, International Trade Group, Crowell & Moring

Through Section 232, Trump has installed 50% levies on steel and aluminum imports, 25% duties on cars and auto parts and, most recently, a range of tariffs on furniture and other wood products. Those levies resulted from Section 232 investigations, which must be completed before applying the tariffs. The Trump administration is conducting several other Section 232 probes, including on semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and critical minerals.

“One of the reasons why it's launching so many [Section] 232 investigations is so that the backstop already is in play because Section 232 was upheld by both the Court of International Trade and the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit with regard to steel and aluminum tariffs in the first Trump administration,” said Greg Husisian, a partner with law firm Foley & Lardner.

According to Husisian, goods covered by current Section 232 investigations account for roughly 40% of U.S. trade, meaning the potential impact of tariffs based on such probes would be substantial by themselves even if Trump’s use of IEEPA is struck down.

Section 301

Another tool Trump has utilized during both of his terms to enact tariffs is Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Through this mechanism, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative conducts a review over 12 to 18 months to determine whether tariffs or other remedies may be required to combat unfair trade practices of certain countries.

Trump used Section 301 to charge tariffs on imports from China during his first term. Former President Joe Biden later upheld and expanded those levies to include products such as electric vehicles, batteries and semiconductors.

Similar to Section 232, tariffs enacted through Section 301 investigations have previously received judicial backing. The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in September upheld Trump’s use of Section 301 to impose tariffs during his first term.

Given such precedent for Section 232 and Section 301, there is reason to believe the Trump administration will be even more aggressive in pursuing such avenues for new tariffs.

“I think initially I would expect to see more heavy reliance on Section 232 and 301,” said Kelsey Christensen, an international trade attorney at Clark Hill.

Section 338

Another potential tool the Trump administration could utilize is Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930. The statute allows for the imposition of tariffs of up to 50% via presidential proclamation in response to discrimination by another country against U.S. commerce. The president also has the power to revoke and amend any tariffs implemented.

However, this provision has not been used since the 1940s and could face pushback from the World Trade Organization, according to Schaefer. However, due to the current lack of a WTO appellate body, the U.S. could appeal any panel review decision “into oblivion,” he added.

Section 201

While Section 338 allows for broader executive discretion, Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 is “a safeguard investigation,” according to Christensen.

A Section 201 proceeding is initiated by a petition, including government-led ones. The tool requires a roughly six-month investigation by the U.S. International Trade Commission to determine if a “material injury” is being done to a specific domestic industry, per Schaefer.

“It's a little like a dumping case, except instead of proving, what has to be shown is, in an open case, that there's material injury,” Schaefer said.

President George W. Bush used this tool to impose steel tariffs during his presidency, according to Schaefer. Similarly, a Section 201 petition by Harley-Davidson in the 1980s led to 45% tariffs on motorcycles from Japan.

Section 122

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 gives the president authority to quickly install tariffs due to a trade deficit, similar to how Trump has used IEEPA. However, the provision has more rigid guardrails. The duties can be no more than 15% and expire after 150 days unless Congress approves an extension, according to Schaefer.

“Fifteen percent isn't as high as some of the rates on some countries, but it actually is the rate for a lot of countries,” Schaefer said in reference to current country-specific levies. “And so you can imagine [Trump] using that to splice in place of what he's done now.”

Editor’s note: This story was first published in our Procurement Weekly newsletter. Sign up here.