There is “no clear evidence” that the Trump administration’s tariff policies have swayed U.S. fashion companies to up domestic sourcing, according to a 2025 Fashion Industry Benchmarking Study published from the U.S. Fashion Industry Association.

Each of the 25 fashion companies surveyed between April and June for the report said they expect higher tariff and trade barrier costs this year. Around 70% of respondents reported that they had delayed or canceled sourcing orders due to tariff hikes from the Trump administration.

So far, adjusting procurement networks has been the most commonly adopted tariff mitigation strategy, per the study, with more than 80% of respondents saying that they would diversify their production footprint to other countries and regions.

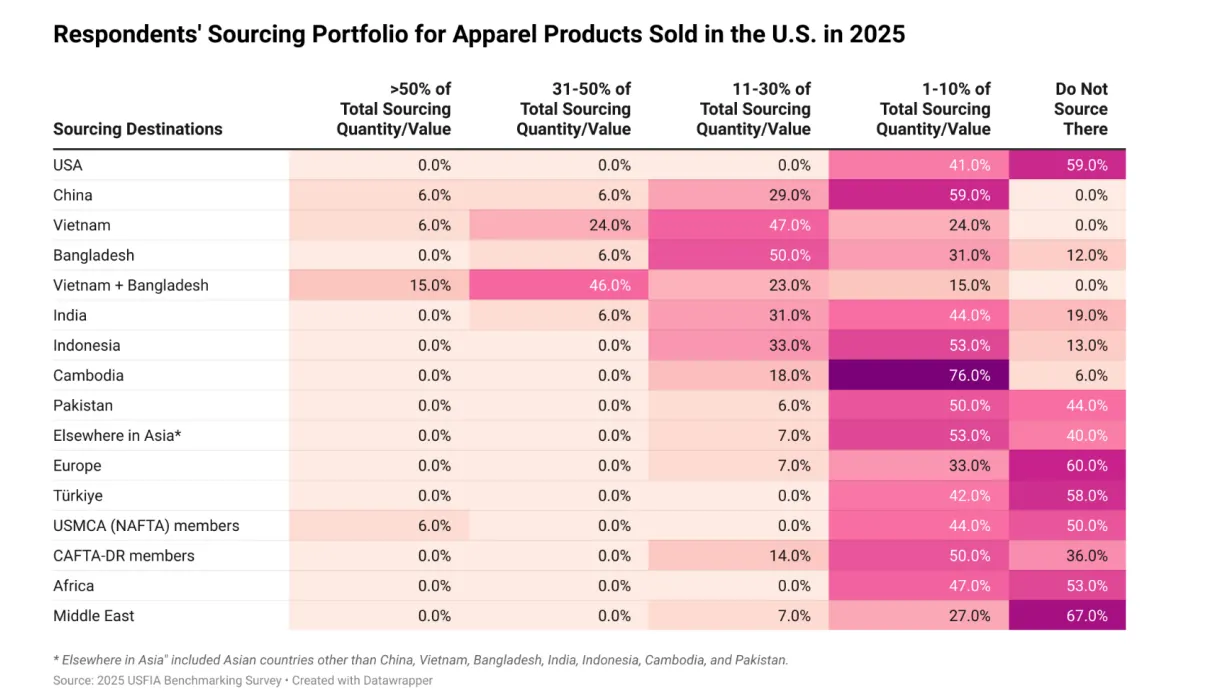

About 44% of respondents explicitly stated they would expand sourcing from the Western Hemisphere, while 17% plan to source more ‘Made in the USA’ apparel and textiles, per the study, which was published in July. Meanwhile, about 40% of surveyed respondents said they sourced goods from the U.S., matching the percentage from the 2024 version of the report.

“Higher tariffs can directly disadvantage U.S.-based production,” report author Sheng Lu, a professor at the University of Delaware’s department of fashion and apparel studies, told Supply Chain Dive in an email. “A U.S. company may manufacture the clothes here, but use yarns, fabrics, and zippers from other countries. When tariffs drive up the cost of these raw materials, it reduces the price competitiveness of apparel ‘Made in the USA.’”

But that doesn’t mean U.S. fashion brands aren’t interested in shifting production to the Western Hemisphere — there are just major challenges to address.

Sourcing hurdles

Asia continues to be the dominant apparel sourcing base for U.S. fashion companies, per the USFIA report. While brands and retailers have reduced or aim to reduce China sourcing to low single-digit percentages this year and beyond, per the report, several other countries in the continent have become increasingly attractive, including Vietnam, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Indonesia.

“Additionally, compared to key Asian suppliers, U.S. domestic suppliers were often seen as lagging in product diversity, agility, flexibility, and vertical integration — the exact factors that are increasingly vital for U.S. fashion companies navigating today’s uncertain trade environment,” Lu said.

As Lu noted, the state of U.S. textile production remains a major barrier to domestic sourcing. Between January and July, U.S. production of textiles such as fibers, yarns and fabrics, decreased 6.2% while U.S. apparel production fell by 4.3%, Lu said.

“In other words, no evidence shows that hiking tariffs has benefited U.S. domestic textile and apparel production,” Lu added.

In turn, the shrinking pool of overall sourcing has hindered orders for U.S.-based producers, which account for less than 10% of a typical fashion company’s sourcing footprint, he said. U.S. yarn and fabric exports to trading partners in the Western Hemisphere, including Mexico and members of the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement, dropped between 8% to 10% in the first five months of the year. This means that garment exports from those countries — which use U.S.-origin textiles — have slowed.

Additional challenges exist for U.S. fashion brands attempting to source sustainably from domestic suppliers. Although most companies are likely to source clothing made with sustainable textiles in the U.S., including recycled, organic or regenerative materials, new infrastructure investments are still needed to up production capacity, Lu said.

“To truly support ‘Made in the USA,’ U.S. trade policy needs to go beyond punitive tariffs and focus on long-term strategies that encourage innovation and investment at home,” Lu said.

Persistent uncertainty

Given trade policy uncertainty, many domestic factories are in “wait and see” mode and refraining from investing in the type of production expansion projects needed to grow production capacity in the U.S., Mexico and CAFTA-DR countries, according to Lu. Therein lies the challenge, as brands have limited control over what and where suppliers produce materials.

“It really is up to the supplier and vendor to decide they’re going to move operations or open up new operations,” Beth Hughes, American Apparel and Footwear Association VP of trade and customs policy, told Supply Chain Dive.

Hughes said that factory owners won’t build new facilities or upgrade product lines if contracts aren’t in place. Further, brands and retailers will hesitate to commit to a long-term contract if they can’t see finished products or anticipate trade policy shifts.

Meanwhile, investors have generally been able to build up infrastructure in Asia a lot faster than in the Western Hemisphere, Hughes said. However, she added that some Asia-based suppliers and vendors have been making the move to Central America.

Labor also presents a hurdle for domestic sourcing, Hughes said. The workforce to support expanded domestic sourcing would not only require specific technical skills but would need to be “willing to do that kind of job.”

Overall, the U.S. lacks the infrastructure to boost domestic sourcing capabilities, Hughes said. Despite some efforts from brands and retailers, most clothes and shoes are imported. Although that might change, Hughes said it would take a “lot of capital; a lot of time.”