Editor's note: This is the second story in a series exploring how the proposed Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern combination could affect shippers. Read the first story on intermodal shipments here.

While Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern say their combined network could speed up various types of shipments, carload traffic is expected to benefit the most.

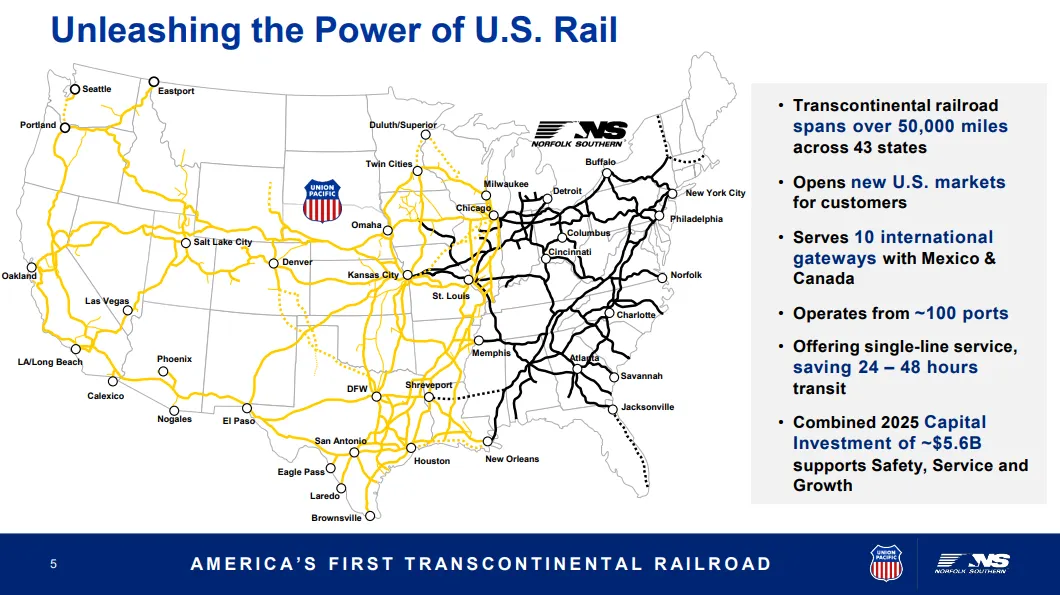

Transit time could be reduced by up to two days for carload shipments that the railroads currently exchange at east-west gateways — such as Chicago and New Orleans. And that, they say, will make rail more competitive with trucks while improving reliability and reducing costs for shippers. Plus, the faster service should translate into lower inventory carrying costs while enabling customers to shrink their freight car fleets, the railroads claim.

But some shippers are skeptical, citing prior mergers that failed to deliver on promised service improvements.

How UP and NS plan to speed carload shipments

The potential reduction in transit time is expected to be greatest for carload traffic that currently requires the most handling and often suffers the longest interchange delays at east-west gateways such as Chicago.

A combined, transcontinental railroad could in theory speed carload shipments by eliminating delays related to interchange and by controlling service design for a car’s entire trip from origin to destination. For example, UP could eliminate as many as four intermediate handlings for a load of lumber moving from an NS-served mill in the Southeast to a distributor in Phoenix on UP, CEO Jim Vena said in an August interview.

Switching cars fewer times should improve service reliability simply by reducing the potential for missed train-to-train connections, said C. Tyler Dick, an assistant professor associated with the Texas Railway Analysis & Innovation Node at the University of Texas at Austin.

It should also improve equipment utilization as cars move faster and more consistently through the system. And yet, carload trip times and car utilization haven’t improved much, Dick said, despite the dozens of mergers since 1980 that created modern railroad networks.

“However, the previous consolidations did little to improve the key east-west gateways, which is what the UP-NS merger is banking on,” he said.

Experts remain skeptical about service promises

Despite the railroads' aspirations, how they connect in Chicago and other gateways could dampen hopes for service improvements. Those interchanges have traditionally been a wild card due to frequent congestion and limited crew availability, according to a long-tenured and retired rail executive familiar with the railroads' Chicago terminals and operating practices, who would only speak on the condition of anonymity given the sensitivity of rail operations.

A North Platte-Bellevue train, for example, would have two routing options through the Windy City, the retired executive said. One would be under UP-NS control but would face rush hour conflicts with commuter trains. The other doesn’t tangle with commuter trains but isn’t entirely under the control of either railroad.

“Keeping the trains moving (even slowly) through interchange points saves more than 24 hours,” the executive said in an email. “However, UP and NS have poor connections at most interchange points, especially at Chicago, so these savings are not automatic.”

In general, railroad mergers have not lived up to their service-related promises, Chris Jahn, CEO of the American Chemistry Council, said in an interview.

In theory, single-line service should cut transit times and enable shippers to use fewer cars, Jahn said. “But we just haven’t seen that in reality,” he said of previous mergers.

A rail logistics manager for a major energy company, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was concerned about retribution from railroads, agreed. The rail logistics manager said prior mergers have not produced the transit time reductions necessary to allow the energy company to shrink its tank car fleet.

“You really have to look at it by individual origin-destination pairing,” the rail logistics manager said in an interview. “There’s some incremental improvement here or there, but on the macro level, I would say it’s not been appreciable at all.”

There’s nothing stopping the railroads from operating direct run-through trains today, the rail logistics manager said, noting that 25 years ago all Class I systems routinely built trains that ran deep into each other’s networks.

But since 2000, carload volume has dropped by more than 20% in the East, according to data that NS and CSX provide to the Association of American Railroads. “You don’t have the volume between city pairs to run direct city-to-city trains across Chicago with seamless service, regardless of whether you put UP and NS together,” the rail logistics manager said.

Where there is volume, other railroad pairings have successfully launched direct routes that speed carload transit times.

Carload traffic has been booming in Western Canada thanks to growth in petrochemicals and energy-related traffic such as frac sand, steel pipe and natural gas liquids. In turn, Canadian National and NS in 2017 launched two pairs of run-through merchandise trains between CN’s yard in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and the NS yard at Elkhart, Indiana.

The direct move, which avoids Chicago terminal congestion by using CN’s unique bypass around the city, saves 48 hours compared to the prior interchange arrangement.