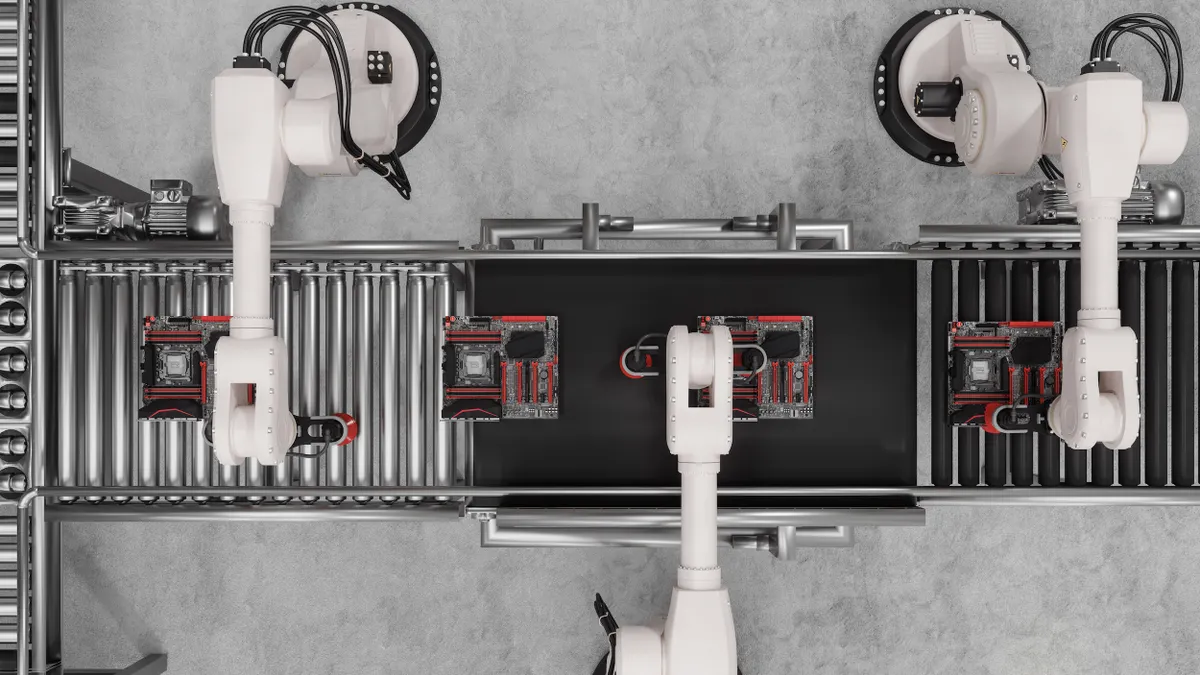

The semiconductor shortage created over the ownership of the chip manufacturer Nexperia in the Netherlands is not just a governance dispute, it’s a warning shot across the bow for the automotive industry.

That’s the view of Moody’s Supply Chain Director Sapna Amlani, who believes automakers have to build more varied and robust supply chains to avoid similar disruptions.

The crisis at Nexperia began when the Dutch government seized temporary control of the China-owned company citing security concerns. China responded by stopping exports of semiconductors to the company until a settlement was reached in November.

However, the risk to supply chains for automakers remains an active threat to vehicle production, said Amlani in an email to WardsAuto.

“For procurement leaders, this is more than a temporary disruption,” she said. “It signals a structural risk: geopolitical decisions can instantly reshape sourcing economics. Even with China easing restrictions, governance breaches and quality concerns persist. Future risks could come from tighter EU controls or retaliatory measures from Beijing.”

Here’s what else Amlani shared about how automakers can prevent further supply and production disruptions in a follow-up email.

Q. What can automakers do to prevent geopolitical disruptions impinging on production?

Even after the Nexperia settlement, operational frictions persist, according to Amlani, as the company could not resume wafer exports immediately because of internal disputes between its EU and China units, “highlighting that corporate conflicts can disrupt supply chains as much as geopolitical events.”

Amlani further noted that trade issues spurred by U.S. vehicle and vehicle parts tariffs and shifting company commitments to increase production capabilities in the U.S. must be taken into consideration.

“Supply leaders should plan for multiple scenarios, with and without broad exemptions,” she said.

Amlani suggested two courses of action that automakers can adopt to address current and future geopolitical disruptions, including diversifying the sourcing of key vehicle components, such as semiconductors, while “treating governance and ownership transparency as primary risk factors.”

Her second suggestion is to take measures to use real-time visibility to look beyond Tier 1 contract suppliers to secure better relationships with so-called N-tier suppliers.

Q. What does a multi-sourcing strategy look like and how does it impact quality control?

To secure more robust supply chains, Amlani said: “Many companies are now considering multi-sourcing as a key strategy for building resilience.”

This involves having dual or tri-sourcing across geographic regions and, thereby, distributing risk across suppliers in Southeast Asia, Europe and North America.

It also means manufacturers must standardize core component specifications by having a “Production Part Approval Process” compliance, including design documentation, engineering change documentation, material certifications, dimensional results, process flow diagrams and control plans.

This process requires the production of “golden samples” to ensure quality assurance, supplier accountability and risk reduction, Amlani said.

Automakers also need to adopt traceability tools and analytics, such as Internet of Things, blockchain and quality assurance drift detection to unearth any slight changes in component manufacturing “to validate compliance across suppliers at all times,” she said.

“The 2021 chip shortage, which led to significant earnings cuts across the automotive industry, underscores the importance of multi-sourcing,” Amlani said.

Q. How often should supply chains be stress tested and is the investment worth it?

“Stress-testing has evolved from being a procurement project to a core capability embedded into the operating rhythm of resilient organizations,” Amlani said.

A model for automakers to follow would include a schedule of regular checks, including annual testing for the entire supply chain and quarterly tests targeting critical components such as semiconductors and electric vehicle batteries.

Amlani said these tests should evaluate how quickly operations can restart and how long production can sustain without a key input. Scenarios explored should also include export freezes, wafer shipment halts, tariff escalations, and governance or internal disputes.

She added that the return on investment is clear and proven. “The cost of the 2021 chip shortage alone far exceeds the expense of maintaining a standing stress-test program,” Amlani said. “In fact, in many cases, the investment is recouped with just one avoided disruption.”