Editor's Note: The following is a guest post written by Micah Mallace, Director of Strategic Projects for the South Carolina Ports Authority. A previous version of this post incorrectly spelled Mr. Mallace's name as "Wallace."

Whac-A-Mole is an arcade game that was popular in the 80s in which the player bops toy moles into their holes only to have others pop up elsewhere on the board. It’s also how some companies manage supply chains — they pursue cost savings in one area only to see costs go up somewhere else.

To mitigate cost in a supply chain, a company must tailor their supply chain strategy to their business needs. Second, they must understand their landed cost for that product. When companies do neither, they pursue savings on individual cost factors in their supply chains only to incur cost increases elsewhere.

A supply chain strategy requires a company to consider the goal of their supply chain and organize around that goal. For example, the potential cost a plant shutdown in a Just-In-Time (JIT) manufacturing facility may dictate that on-time delivery is the number one goal to prevent the added costs associated with shutting down the production line.

In this case, the additional costs associated with the highest level of supply chain reliability should be part of the strategy for this company. Vice versa, if a company sells a low margin, high volume base commodity, on-time delivery will be secondary to cost mitigation.

For less critical items, an occasional stock out may be bearable in the name of significant cost reduction and the supply chain strategy will be different than for those critical items. If the company does not distinguish between these types of products in their supply chain, money is wasted on products that don't necessitate “always in stock” costs.

Oftentimes companies have multiple supply chain strategies based on different product lines. For example, Walmart identifies items that consumers require on shelves or they'll shop elsewhere. These items carry a higher opportunity cost and thus move through the supply chain more expeditiously carrying more cost. The added supply chain dollars are offset by higher sales turns.

Understanding landed costs

The bedrock of a supply chain strategy is a fundamental understanding of landed cost. Landed cost is the aggregated costs of sourcing and delivering a product to the end user. This could be a retail shelf, e-commerce doorstep or manufacturing line. A landed cost calculation does not only account for the purchase price and transportation costs, but also inventory carrying costs, tariffs and a risk variance associated with stock-outs or line shutdowns, among others.

Oftentimes, companies compartmentalize cost and make decisions based on individual cost segments of a product. For example, a South Carolina manufacturing facility might have the option to buy components from suppliers in Japan or Tennessee. If the products are the same price, but transportation costs from Japan are higher, then Tennessee seems logical. However, if the Tennessee supplier has a poor record for on-time delivery and the company must carry more inventory to avoid a plant shutdown, the landed cost calculation might favor the Japanese supplier. A company that doesn’t know their all-in landed cost can’t drive effective supply chain strategy.

Although developing a thoughtful supply chain strategy takes time and extra effort, it is a crucial step in managing your supply chain. I spent my first five years at South Carolina Ports Authority in sales calling on large and mid-sized shippers. As members of SC Ports’ Supply Chain Authority, the sales team offers trusted boots on the ground and visibility of ocean, rail, truck and 3PLs. There is no question that the Supply Chain Authority understands our customers’ logistics models.

Time and again, I’ve encountered a micro-focus on reducing a line item rate without understanding the impact on the overall cost. Case in point: I once worked with an importer of furniture that decided to mitigate inventory carrying costs. They focused on transit time and sped up their supply chain. When the cargo arrived in the U.S., the company accrued tremendous demurrage, detention and chassis charges because their distribution center was not fluid enough to handle the increased pace of their inbound freight. Supply chain costs increased because they weren’t looking at the big picture, the total end-to-end supply chain.

Creating a supply chain strategy based on landed cost

To build a supply chain strategy, the pertinent areas within a company (purchasing, transportation and operations) must jointly determine cost inputs and agree on a strategy that meets the company’s goals. The sales department can offer the cost of a stock out, the transportation department the cost of air versus ocean, the purchasing department can focus on leveraging their freight spend rather than using the buying power of a larger supplier. Once an agreed upon cost and strategy are identified, changes should be measured against that strategy.

To ensure sustainable supply chain savings are found within the confines of an agreed upon supply chain strategy, each business segment (purchasing, transportation, supply chain...) should be incentivized and measured by an overlapping metric(s). It is important to incentivize behavior with complimentary, common metrics.

For example, I worked with a major consumer goods company that identified a way to consistently save $2 million per year with no negative impact to total cost or delivery. A good solution, but the transportation department decided against implementing the solution – even though it would have reduced the organization’s overall costs – because the savings would have benefitted the P&L of a different department. It is critically important that companies adopt incentives encouraging internal functional areas to work together to measurably reduce costs.

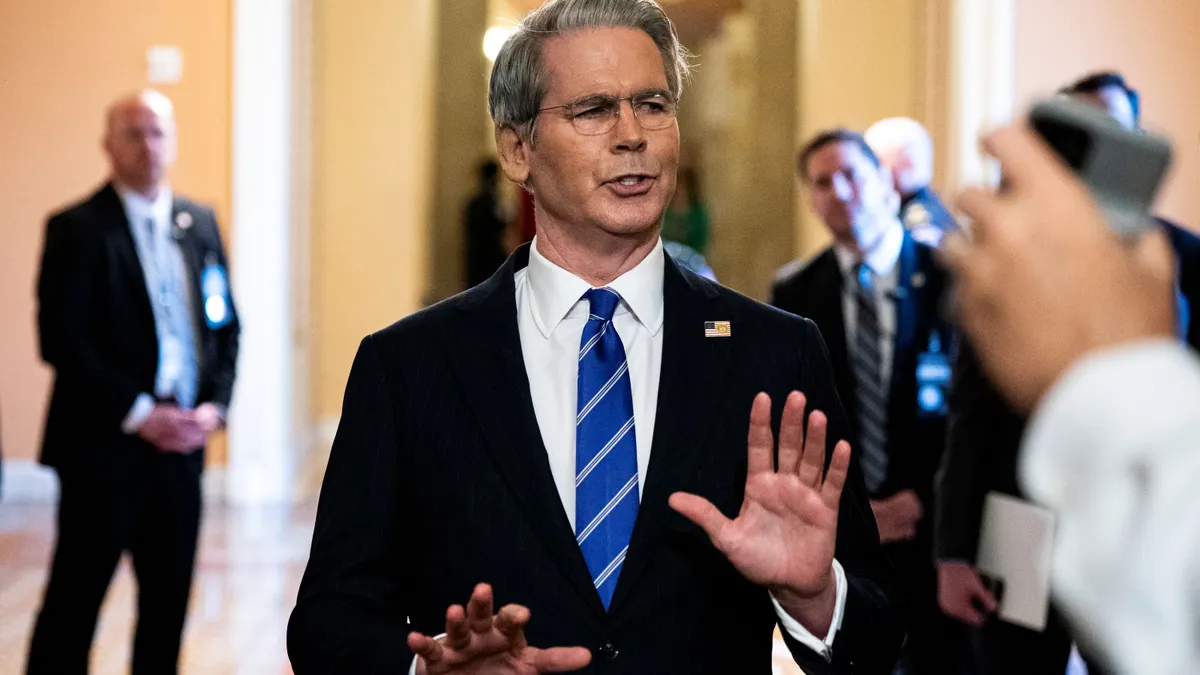

Micah Mallace is the Director of Strategic Projects for the South Carolina Ports Authority.